I know: it sounds like a report you’d have to do in school, like the dreaded and mythological “What I Did With My Summer Vacation.” I don’t remember actually writing one of those on that subject, so this is me making up for it… sorta. Don’t worry. I’ll try to keep it from actually being boring.

I know: it sounds like a report you’d have to do in school, like the dreaded and mythological “What I Did With My Summer Vacation.” I don’t remember actually writing one of those on that subject, so this is me making up for it… sorta. Don’t worry. I’ll try to keep it from actually being boring.

I served in the Army from 1983 to 1987, with a two-year stint in the National Guard after that. It was a peaceful time to be in the service, for the most part, despite it being during the Cold War with the USSR. There were a couple scares while I was in: we invaded Grenada while I was in basic training, prompting rumors that we would not be going to AIT (Advanced Individual Training) but would ship promptly to Grenada upon graduation. Of course, that didn’t happen, and I’d largely forgotten about it by the time I made it to AIT (they keep you busy). Then, sometime later, we bombed Libya. I was stationed at Fort Polk by then, and the base went on alert, but we mostly found out about it on the news.

I was by no means an exemplary soldier. I joined to learn to be a mechanic, but what I really learned was that I have little aptitude for the job—and I don’t much like it besides. So much for that idea. I’m from Arkansas, took basic and AIT at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and was stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana. If you’ll look at an atlas of the US, you’ll see I never got more than a state away from my home.

So much for seeing the world.

To be fair, I did go to Germany for forty-five days in 1984 for an exercise called REFORGER, Armyspeak for Return of Forces to Germany—basically practicing for the Soviets invading Europe through the Fulda Gap. And I made two trips to Fort Irwin, California for OPFOR—Opposing Forces—training. Of a sort. We were observers. Fort Irwin and OPFOR used the tactics and vehicles of the Soviets for our units to go into mock combat against. From what I understand, OPFOR won every time. Not sure what that says about the readiness of our troops in the eighties. Probably a good thing we didn’t go to war with Russia.

To be fair, I did go to Germany for forty-five days in 1984 for an exercise called REFORGER, Armyspeak for Return of Forces to Germany—basically practicing for the Soviets invading Europe through the Fulda Gap. And I made two trips to Fort Irwin, California for OPFOR—Opposing Forces—training. Of a sort. We were observers. Fort Irwin and OPFOR used the tactics and vehicles of the Soviets for our units to go into mock combat against. From what I understand, OPFOR won every time. Not sure what that says about the readiness of our troops in the eighties. Probably a good thing we didn’t go to war with Russia.

I say all this to bring us to this point: because nothing special ever happened during my time in service, Veteran’s Day has never meant a lot to me on a personal level. Being a veteran, of course, I honor those who serve, but when I’m thinking of that, I’m thinking of those who saw combat, or were at least in an MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) that could put them in harm’s way at a moment’s notice.

I was a mechanic. I served my time, got out. End of story.

That changed for me this year, thanks to my wife.

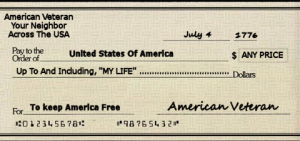

I told her basically what I’ve told you above, and she responded by telling me that, until her younger brother joined the Army, there were no veterans in her family, not since a couple generations back. And when her brother joined, her mother was very opposed to it, even though it was during peacetime, because of one thing: when you join any branch of the military, you’re writing a blank check on your life, payable at any time during your service, payment to include death, if necessary.

you’re writing a blank check on your life, payable at any time during your service, payment to include death, if necessary.

Yeah, we’ve seen that on Facebook and other social media for years now. God knows I’ve read it often enough. But I guess the real meaning of that never sunk in. It was like, even though I signed that same blank check, because nothing happened during my tour, it didn’t really apply to me. I didn’t go to Nam, or Grenada, or Mogadishu, or Iraq. I was never in combat, never even close except for being an observer in some war games (we accidentally drove into the middle of a “battle” between tanks and helicopters one of my trips to Fort Irwin).

My wife told me that didn’t matter. What counted to her was that it could have happened. I was vaguely aware of that when I went in, of course, but was victim to that syndrome where you think it can never happen to you. Luckily, it didn’t. But it put those incidents in Grenada and Libya into a new perspective for me.

It could have been me going to Grenada. I could have been called up for something, who knows? You join during peacetime, but you never know what can happen in this world. Just ask those guys who were in those barracks in Lebanon in the early eighties. Or, more recently, the recruiters who were shot while simply standing on the sidewalk. Here in America. You shouldn’t have to worry about being shot while you’re a recruiter.

It could have been me going to Grenada. I could have been called up for something, who knows? You join during peacetime, but you never know what can happen in this world. Just ask those guys who were in those barracks in Lebanon in the early eighties. Or, more recently, the recruiters who were shot while simply standing on the sidewalk. Here in America. You shouldn’t have to worry about being shot while you’re a recruiter.

The penultimate moment for me came on Veteran’s Day itself when we visited Pea Ridge Battlefield, a site dedicated to one of the few Civil War battle sites west of the Mississippi. We were in the visitors’ center when I saw they had a DVD documentary of the battle. My wife hugged me and said to pick it or one of the books offered for sale there as a Veteran’s Day gift.

A Veteran’s Day gift? For me?

I’ll be honest: I choked up. I’m choking up a little writing about it.

I didn’t know what to say, so I finally just hugged her back and said, “Thank you.”

My wife later told me she had known plenty of guys who joined back when I did and didn’t even make it through basic training. That’s probably when I saw my service for what it was. I joined. I served. I stuck with it, even when all I wanted to do was chuck my uniforms and go home. Basic training was the worst, because I’d been raised sheltered and was suddenly thrust into an entirely different culture. I felt lost and alone. Phone calls home were a lifeline to something sane and familiar.

But I didn’t quit. What would people back home think if I did? I couldn’t allow that to happen. I’d made a promise, signed my name on the bottom of that blank check. I would fulfill my promise, cash in that check if necessary.

Thank God it never was.

Sunday and Monday, at odd moments, I kept thinking of Pea Ridge. One of the stops on the tour is Elkhorn Tavern, used by both sides as a makeshift hospital, and reading of how some Confederate troops marched overnight from a fight at the now-nonexistent Leetown to Elkhorn Tavern—a distance we covered in mere minutes in my pickup—to join the main battle. It took them ALL NIGHT to march perhaps four miles. I stood on the ground where those men fought and bled and died, all within sight of the tavern, on a cold March day in 1862. The weather was chilly, and it helped a bit to relate.

Tavern—a distance we covered in mere minutes in my pickup—to join the main battle. It took them ALL NIGHT to march perhaps four miles. I stood on the ground where those men fought and bled and died, all within sight of the tavern, on a cold March day in 1862. The weather was chilly, and it helped a bit to relate.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not elevating myself up with the guys who fought there, or at Normandy, or Ia Drang Valley, or Chosin Reservior, or Kuwait, or who endured the infamous Mogadishu Mile or the Bataan Death March. Or the Hanoi Hilton. Or Dachau. Or Auschwitz. Or any other battle or POW camp.

But I was made to realize that I stepped up. I served. I probably know fewer veterans than I do non-veterans. I’m not saying that as a judgment, just an observation.

I’m proud of my service. And for the first time, I feel that service was appreciated by someone very close to me for Veteran’s Day.

I’ll close by saying a big, belated thank you to all those who went into harm’s way to serve, who went farther down that trail than I did so that I can remain free.

I’ll close by saying a big, belated thank you to all those who went into harm’s way to serve, who went farther down that trail than I did so that I can remain free.

May the sun shine on your face, the wind be at your back, and may you be in heaven long before the devil knows you’re dead.

Later,

Gil